Amongst the many publications relating to the victorious career of Gustavus Adolphus, king of Sweden, there was one entitled the Swedish Intelligencer,

printed at London in 1632, for Nathaniel Butter and Nicholas Bourne,

both of them names associated with the first establishment of newspapers

in England. The Swedish Intelligencer gives very full accounts

of the exploits of Gustavus, and it is illustrated with his portrait, a

bird’s-eye view of the siege of Magdeburg, a plan showing how the King

of Sweden and his army crossed the river Lech into Bavaria, and a plan

or bird’s-eye view of the battle of Lutzen, where Gustavus was killed.

The portrait, the siege of Magdeburg, and the battle of Lutzen, are

engraved on copper, but the passage of the Lech is a woodcut. I have

copied the latter, the others being too elaborate for reproduction on a

reduced scale. The three last named are very curious as illustrations of

war news. Gustavus had crossed the Danube, and his troops overspread

the country between that river and the river Lech. Field Marshal Tilly

was in front of him, waiting for reinforcements from the army of

Wallenstein, in Bohemia, and the junction of fresh levies raised in

Bavaria, with which he hoped to drive the invaders back across the

Danube. The account in the Swedish Intelligencer of this celebrated

passage of the River Lech is too long for quotation, but I give a

condensed version of the circumstances from other sources.

The

Lech takes its rise among the mountains of the Tyrol, and, after

washing the walls of Landsberg and Augsburg, falls into the Danube at a

short distance from the town of Rain. The banks are broken and

irregular, and the channel uncertain. Nor are there many rivers of the

same size in Germany which can be compared with it in the strength and

rapidity of its current. The united forces of Bavaria and the League,

with this efficient means of defence in front, extended their right wing

towards the Danube and their left towards Rain, while the banks of the

river, as far as the city of Augsburg, were observed by their patrols,

supported by detached bodies of infantry. Tilly had taken the precaution

of breaking down the bridges over the Lech, and had thrown up field

works at points where he judged the passage might be considered attended

with fewest difficulties. That the Swedes would attack him in his main

position was a pitch of daring to which, well as he was acquainted with

the enterprising spirit of the king, he could scarcely suspect him of

having yet attained. Such, however, was the full determination of

Gustavus. After he had reconnoitred the course of the Lech for some

miles, at the imminent peril of his life, he fixed upon a point between

Rain and Thierhauppen, where the river makes a sweep to the eastward, as

the spot for carrying his venturous design into effect. The king’s

first intention was to throw a floating bridge over the stream, but the

attempt was no sooner made than it was found to be rendered hopeless by

the rapidity of the current. It was then imagined that tressels might be

sunk, and firmly secured by weights in the bed of the river, on which

the flooring of the bridge might afterwards be securely laid. The king

approved of this plan, and workmen were commanded to prepare the

necessary materials at the small village of Oberendorf, situated about

half a mile from the spot. During the night of the 4th of April the work

was entirely finished, the supports fixed in the stream, and the planks

for forming the bridge brought down to the water’s edge. The king had,

in the meantime, ordered a trench to be dug along the bank of the river

for the reception of bodies of musketeers, and several new batteries to

be constructed close to the shore, the fire from which, as they were

disposed along a convex line, necessarily crossed upon the opposite

side; those upon the left hand of the Swedes playing upon the left of

the enemy, and those on the right upon the wood held by the Bavarians.

Another battery, slightly retired from the rest, directed its fire

against the entrenchments occupied by Tilly’s centre. By daybreak on the

5th, all necessary preparations having been made, the bridge was begun

to be laid, and completed under the king’s inspection. Three hundred

Finland volunteers were the first who crossed, excited by the reward of

ten crowns each to undertake the dangerous service of throwing up a

slight work upon the other side for its protection. By four in the

afternoon the Finlanders had finished their undertaking, having been

protected from a close attack by the musketry of their own party and the

batteries behind them, from which the king is said to have discharged

more than sixty shots with his own hand, to encourage his gunners to

charge their pieces more expeditiously. The work consisted merely of an

embankment surrounded by a trench, but it was defended both by the

direct and cross fire of the Swedes. As soon as it was completed,

Gustavus, stationing himself with the King of Bohemia at the foot of the

bridge, commanded Colonel Wrangle, with a chosen body of infantry and

two or three field-pieces, to pass over, and after occupying the work,

to station a number of musketeers in a bed of osiers upon the opposite

side. The Swedes crossed the bridge with little loss, and after a short

but desperate struggle the Imperialists were routed. The whole of the

Swedish army was soon upon the eastern bank of the Lech, where the king,

without troubling himself with the pursuit of the enemy, commanded his

army to encamp, and ordered the customary thanksgivings to be offered

for his victory.

The account in the Swedish Intelligencer

is wound up in these words: ‘And this is the story of the King’s bridge

over the Lech, description whereof we have thought worthy to be here in

Figure imparted unto you.’ Then follows an ‘Explanation of the Letters

in the Figure of the Bridge,’ given below the illustration. The

engraving does not appear to have been entirely satisfactory to the

author, for on its margin the following words are printed: ‘Our Cutter

hath made the Ordnance too long, and to lye too farre into the River.

The Hole also marked with R, should have been on the right hand of the

Bridge.’

|

| PASSAGE OF THE RIVER LECH, BY GUSTAVUS ADOLPHUS. FROM THE ‘SWEDISH INTELLIGENCER,’ 1632 |

REFERENCES TO PASSAGE OF THE RIVER LECH.

A The King of Sweeden, and the King of Bohemia by him.

B The Bridge.

C

A Trench or Brestworke, in which the Kings Musketeers were lodged,

betwixt the severall Batteryes of the great Ordnance, which Musketeers

are represented by the small stroakes made right forwards.

D Divers little Field-pieces.

E Plat-formes or Batteryes for the Kings greater Cannon.

F

The Halfe-moone, with its Pallisadoe or Stocket, beyond the Bridge, and

for the guard of it. It was scarcely bigge enough to lodge a hundred

men in.

G A little Underwood, or low Bushy place.

H A plaice voyd of wood; which was a Bache, sometimes overflowne.

I A Brestworke for Tillyes Musketeers.

K K Tilly and Altringer; or the place where they were shot.

L The high wood where the Duke of Bavaria stood.

M Tilleyes great Batteryes to shoot down the Bridge.

N A small riveret running thorow the wood.

O Tillyes great Brestworke; not yet finished. Begun at sixe in the morning; and left off when he was shot.

P Some Horse-guards of Tillyes: layd scatteringly here and there all along the river from Rain to Augsburg.

Q The kings Horse-guards, and Horse-sentryes.

R A hole in the earth, or casual advantageable place; wherein some of the Kings Foot were lodged.

S The Hill behind Tillyes great worke.

T The fashion of the Tressels or Arches for the Kings Bridge.’

In 1636 the Sallee Rovers

had become very troublesome, and not only hindered British commerce on

the high seas, but even infested the English coasts. They had captured

and carried into slavery many Englishmen, for whose release a ‘Fleete of

Shippes’ was sent out in January 1636. Assisted by the Emperor of

Morocco, the nest of pirates was destroyed and the captives released. A

full account of this expedition is given in a curious pamphlet,

entitled, ‘A true Journal of the Sally Fleet with the proceedings of

the Voyage, published by John Dunton, London, Mariner, Master of the

Admirall called the Leopard. Whereunto is annexed a List of Sally

Captives names and the places where they dwell, and a Description of the

three Townes in a Card. London, printed by John Dawson for Thomas

Nicholes, and are to be sold at the Signe of the Bible in Popes Head

Alley, 1637.’ This tract is illustrated by a large plan of Sallee,

engraved on copper, with representations of six English vessels of war

on the sea. After minutely describing the proceedings of the voyage, and

giving a long list of the captives’ names, the journalist winds up in

these words: ‘All these good Shippes with the Captives are in safety in

England, we give God thanks. And bless King Charles and all those that

love him.’

At the end of the pamphlet is printed the

authority for its publication: ‘Hampton Court, the 20. of October, 1637.

This Journall and Mappe may be printed.’

There is an illustrated pamphlet of this period which I have not been able to see. It is entitled, ‘Newes,

and Strange Newes from St. Christopher’s of a Tempestuous Spirit, which

is called by the Indians a Hurrycano or Whirlwind; whereunto is added

the True and Last Relation (in verse) of the Dreadful Accident which

happened at Witticombe in Devonshire, 21. October, 1638.’

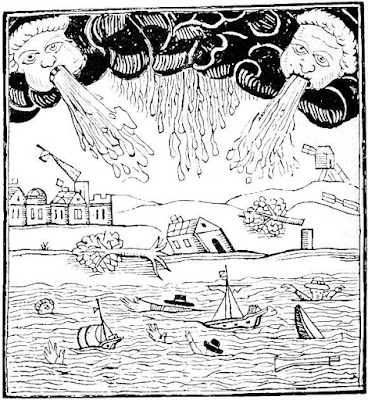

The Weekly News,

begun in 1622, had been in existence sixteen years when the idea of

illustrating current events seems to have occurred to its conductors;

for in the number for December 20, 1638, there is, besides the usual

items of foreign news, an account of a ‘prodigious eruption of fire,

which exhaled in the middest of the ocean sea, over against the Isle of

Saint Michael, one of the Terceras, and the new island which it hath

made.’ The text is illustrated by a full-page engraving showing ‘the

island, its length and breadth, and the places where the fire burst

out.’ I have not been able to find a copy of the Weekly News for December 20, 1638, either in the British Museum or elsewhere. My authority for the above statement is a letter in the Times of October 13, 1868. As far as I have been able to ascertain, no other illustrations were published in the Weekly News,

so that we must conclude the engraving of the ‘prodigious eruption of

fire’ was an experiment, which in its result was not encouraging to the

proprietor or conductors of the journal.

|

| TAKING OF THE CASTLE OF ARTAINE, IRELAND, 1641 |

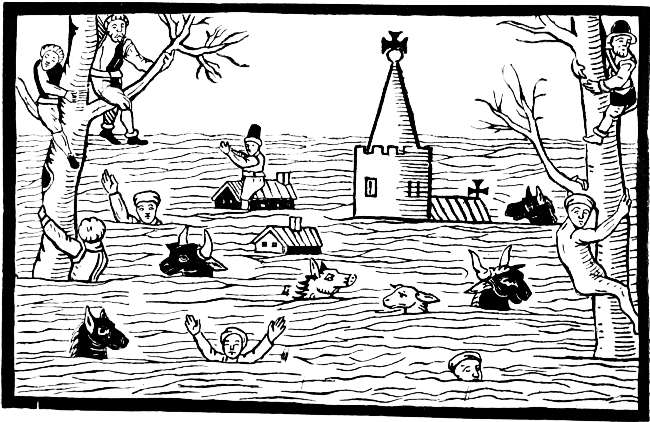

When

the Irish Rebellion of 1641 broke out, many news-books were published

describing the transactions in that country, and several of them are

illustrated. I may here remark that the illustrations of events in these

pamphlets, as well as many of those contained in the numerous tracts

published during the Civil War in England, appear to be works of pure

imagination, and were, probably, invented by the artist just as a modern

draughtsman would illustrate a work of fiction. Others, again, were

evidently old woodcuts executed for some other purpose. A few instances

occur, however, where drawings have been made from actual scenes, and

sometimes maps and plans are given as illustrations of a battle or a

siege. This rising of the Roman Catholics in Ireland began with a

massacre of the Protestants, and, according to the tracts published at

the time, the atrocities of recent wars in Bulgaria and elsewhere were

equalled in every way by the Roman Catholics in Ireland in the

seventeenth century. The illustrations in these tracts are very coarse

woodcuts. One represents the arrest of a party of conspirators, and

another is a view of a town besieged, while a third gives a group of

prisoners supplicating for mercy. The best illustration that I have met

with of this Irish news is contained in a pamphlet entitled, ‘Approved,

good and happy Newes from Ireland; Relating how the Castle of Artaine

was taken from the Rebels, two of their Captaines kild, and one taken

prisoner by the Protestants, with the arrival of 2000 foot, and 300

horse from England. Also a great skirmish between the Protestants and

the Rebels at a place near Feleston, wherein the English obtained great

renowne and victory: Whereunto is added a true relation of the great

overthrow which the English gave the Rebels before Drogheda, sent in a

letter bearing date the 27 of February to Sir Robert King, Knight, at

Cecill house in the Strand. Printed by order of Parliament. London,

Printed for John Wright 1641.’ The woodcut on the title-page of this

tract represents the taking of the castle of Artaine, but there is only

the following very short paragraph relating to it:—‘The last news from

Ireland 7 March 1641. The 10 of February our men went to Artaine against

a castle so called, which had before done some mischiefe, to some of

our men, the enemy being in it. But the enemy fled before our second

coming, and left the Castle, and a garrison was left in it by us.’ The

other news is related more at length, and one of the paragraphs runs

thus:—‘On the 13 a man was brought to our City, being taken by some of

our scattering men scouting about our City, who confest without

constraint, that he had killed an Englishwoman at a place called

Leslipson, 6 Miles West of our City, and washed his hands in her bloud,

being set on by the popish Priests so to doe; he was presently hanged,

but dyed with much repentance and a protestant, which few do.’ The

concluding paragraph of this pamphlet shows the writer to have been a

man of a commercial spirit:—‘Tis to be feared that a famine is like to

be in our City, in that still men come to us and provision is short, and

none of yours that come to us bring any vittailes, great taxes are upon

us, more than can be borne. He that had Butter, and Cheese, and Cloath,

at between 6 and 14 shillings a yard here sent by any out of London

might make a good trade of it. Cheshire Cheese is sould here for

sixpence a pound already. Some of your Londoners are come hither

(acquaintance of mine) that will send for such things, for great profit

may be made by them and quicke returne.’

Several other

pamphlets relating to the Irish Rebellion are illustrated, but, with a

few exceptions, the cuts bear very little relation to the subject, and

were probably not executed for the purpose. One gives an account of a

victory obtained by the English at Dundalk in 1642, and it has a woodcut

of a man firing a cannon against a town, a copy of which is appended.

|

| VICTORY AT DUNDALK, 1642 |

The

description is in the following words:—‘Newes from Ireland. On Monday

morning came three Gentlemen to our City of Dublin from Sir Henry

Tichbourne, who brought a message to the state of a great and happy

victory obtained by the aforesaid Sir Henry Tichbourne with 2000 horse

and foot marched to Ardee, and there put 400 of the Rebels to the sword,

yet lost not one man of our side; from thence upon the Saturday

following, he mustered up his forces against a place called Dundalke

some 14 miles northward from Tredath, where the enemy was 5000 strong,

and well fortified. At his first approach there issued out of the Towne

3000 of the Rebels who all presented themselves in Battallia, our

Forlorne hopes of horse and foot had no sooner fired upon them, but they

routed the Rebels. Captaine Marroe’s Troope of horse setting on killed

great store of the Rebels who thereupon retreated to the Towne, made

fast the gates, and ran out at the other end to their boats beforehand

provided: Our Army coming in fired the gates, entred, and killed those

within. Captain Marroe followed the flying foe, and slew abundance of

them upon the strand, and it is reported by them that if he had known

the Fords and the River, he had cut them all off, if he had gained the

other side of the River, but being a stranger, could not doe it (wanting

a guide) without endangering the Troope. There was slaine of the Rebels

in this sudden skirmish not less than 1100 besides what they took

prisoners. Sir Philomy O’Neale fled with the rest of the Commanders; but

10 common soldiers were lost of our side. Sir Philomy O’Neale made

speed away to a place called Newry, a chiefe garrison of the Rebels. Sir

Henry Tichbourne hath sent 600 men more to Dublin, intending that place

shall be the next he begins withall, which is granted, and tomorrow

there goeth to him 500 men, if not 5000, for whose safety and prosperity

in the meantime is the subject of our daily prayers that he may have as

good success as in all his other designs from the first till this time;

for no man was ever so beloved by his souldiers, that protest to follow

him while they can stand. We are in great hope he will recover the

Newry very shortly; it is credibly reported, that they got 20,000 pounds

at least in pillage at Dundalke.’

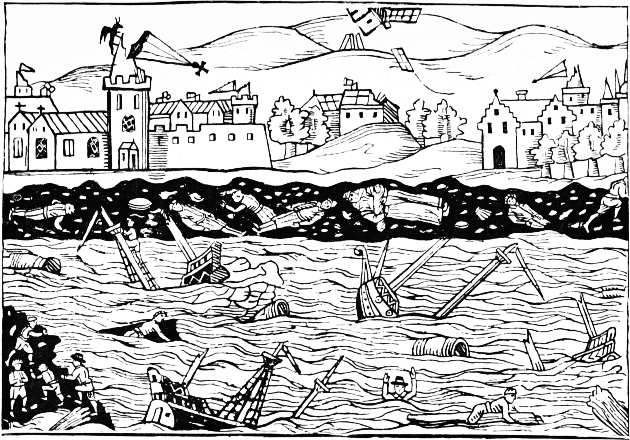

In another

pamphlet, dated 1642, there is an account of a battle at Kilrush, which

is also illustrated with a woodcut. The circumstances are related in

detail, but they are sufficiently set forth in the title, without

further quotation:—‘Captaine Yarner’s Relation of the Battaile fought

at Kilrush upon the 15th day of Aprill, by my Lord of Ormond, who with

2500 Foot and 500 Horse, overthrew the Lord Mountgarret’s Army,

consisting of 8000 Foot and 400 Horse, all well armed, and the choyce of

eight Counties. Together with a Relation of the proceedings of our

Army, from the second to the later end of Aprill, 1642.’

|

| BATTLE OF KILRUSH, 1642 |

Many

other illustrated pamphlets relating to current events were published

at this time. It would appear that in 1641 there was a visitation of the

plague in London, and a tract of that date has reference to it. It is

entitled:—‘London’s Lamentation, or a fit admonishment for City and

Country, wherein is described certain causes of this affliction and

visitation of the Plague, yeare 1641, which the Lord hath been pleased

to inflict upon us, and withall what means must be used to the Lord, to

gain his mercy and favour, with an excellent spirituall medicine to be

used for the preservative both of Body and Soule.’ The ‘spiritual

medicine’ recommended is an earnest prayer to heaven at morning and

evening and a daily service to the Lord. The writer endeavours to

improve the occasion very much like a preacher in the pulpit and

continues his exhortation thus:—‘Now seeing it is apparent that sin is

the cause of sicknesse: It may appear as plainly that prayer must be the

best means to procure health and safety, let not our security and

slothfulnesse give death opportunity, what man or woman will not seem to

start, at the signe of the red Crosse, as they passe by to and fro in

the streets? And yet being gone they think no more on it. It may be,

they will say, such a house is shut up, I saw the red crosse on the

doore; but look on thine own guilty conscience, and thou shalt find thou

hast a multitude of red crimson sinnes remaining in thee.’ I have

copied the illustration to this tract, and it will be seen that it is

divided into two parts—one representing a funeral procession advancing

to where men are digging two graves—the other showing dead bodies

dragged away on hurdles. The first is labelled ‘London’s Charity.’ The

second ‘The Countrie’s Crueltie.’ This was perhaps intended to impress

the reader in favour of the orderly burial of the dead in the city

churchyards, a subject on which public opinion has very much changed

since that time.

|

| THE PLAGUE IN LONDON, 1641 |

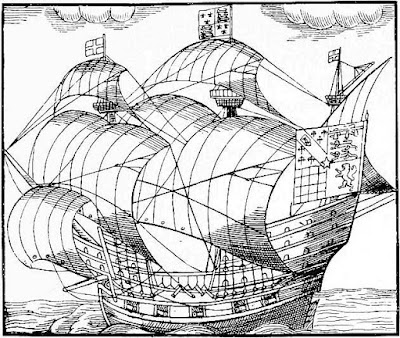

We

have already noticed that the vicissitudes of the sea and the accidents

of maritime life, which supply so much material to modern newspapers,

were not less attractive to the early news-writers. There is a very

circumstantial account of the voyage and wreck of a ship called the

Merchant Royall in a pamphlet published in 1641. The engraving it

contains is the same block used by Thomas Greepe in 1587. It is

entitled, ‘Sad news from the seas, being a true relation of the losse

of that good Ship called the Merchant Royall, which was cast away ten

leagues from the Lands end, on Thursday night, being the 23 of September

last 1641 having in her a world of Treasure, as this story following

doth truly relate.’ Another illustrated pamphlet, dated 1642, contains a long and minute narrative of how a certain ship called the Coster was

boarded by a native of Java, who, watching his opportunity, murdered

the captain and several of the crew, but who was afterwards killed when

assistance arrived from another ship. There is a woodcut representing

the murders, and the title runs as follows:—‘A most Execrable and

Barbarous murder done by an East Indian Devil, or a native of

Java-Major, in the Road of Bantam, Aboard an English ship called the

Coster, on the 22 of October last, 1641. Wherein is shewed how the

wicked Villain came to the said ship and hid himself till it was very

dark, and then he murdered all the men that were aboard, except the

Cooke and three Boyes. And lastly, how the murderer himselfe was justly

requited. Captain William Minor being an eye-witnesse of this bloudy

Massacre. London: Printed for T. Banks, July the 18, 1642.’ The very

full particulars given in this pamphlet show how minute and

circumstantial the old news-writers were in their narratives. It will be

seen by the following extracts that the story has an air of truth given

to it by careful attention to various small matters of detail:—

‘On

Friday the 22 of October last 1641 towards night there came aboard an

English ship called the Coster, in a small Prow (or flat Boat with one

paddle) a proper young man, (a Java, which is as much as to say as a man

born or native of the Territory of Java.) This man, (or devill in mans

shape) with a pretence to sell some Hews, (hatching mischiefe in his

damned minde,) did delay and trifle time, because he would have the

night more dark for him to do his deeds of darknesse. At last he sold 6

Hews for half a Royall of 8 which is not much above two shillings. There

came also another Java aboard, (with the like small Prow or Boat) to

whom he gave the half Royall, sent him away and bade him make haste; he

being asked for what the other Java went for, the answer was that he had

sent him for more Hews and Goates to sell.

‘Night

being come, and very dark, (for it was the last night of the wane of the

Moone) this inhumane dog staid lurking under the half deck having 2

Crests (or dangerous waving daggers) and a Buckler, of which he would

have sold one and the Buckler with it, and as he was discoursing he took

off one of the Crests hefts and put cloth about the tongue of the

Blade, and made it sure fast: on the other Crest he rolled the handle

with a fine linnen cloth to make it also sure from slipping in his hand;

these things he did whilst the Master, Robert Start, Stephen Roberts,

his mate, Hugh Rawlinson, Chirurgeon, William Perks, Steward, James

Biggs, Gunner, and 3 Boys or Youths attending. At supper they were very

merry, and this Caitiffe took notice of their carelessnesse of him to

suffer him to sit on the quarter deck upon a Cot close by them.

‘Supper

being ended about 6 at night the Master went to his Cabin to rest, the

Gunner asked leave to go ashore, (the ship riding but half a mile from

landing.) Afterwards Robert Rawlinson and Perks walked upon the quarter

deck; and the devilish Java perceiving the Master to be absent, he asked

the Boyes where he was, who answered he was gone to sleepe. This

question he demanded 3 or 4 times of the Boyes, and finding it to be so,

he arose from the place where he sate, which was on the starboard side

and went about the Table next the Mizzen Mast (where Roberts, Rawlings

and Perks were walking) with his Target about his Neck for defence

against Pikes, or the like; and his 2 Crests in his hand, and upon a

sudden cries a Muck, which in that language is I hazard or run my death.

Then first he stabd Roberts, secondly he stabd Rawlinson, thirdly

Perks, all three at an instant. After that he let drive at the Boyes,

but they leapd down, and ran forward into the forecastle, where they

found the Cooke, to whom the Boyes related what had happened.’

Further

details are given at great length, showing how the savage continued his

bloody work, and how he was finally overpowered. The narrative thus

winds up:—

|

| MURDERS ON BOARD AN ENGLISH SHIP, 1642 |

‘It

is observable that of all these men that were thus butchered, the

Hel-hound did never stab any man twice, so sure did he strike, nor did

he pursue any man that kept clear of his stand under the quarter-deck.

So there dyed in all (in this bloody action) Robert Start, Master,

Stephen Roberts, his Mate, Hugh Rawlinson, Chirurgeon, William Perks,

Steward, Walter Rogers, Gunner’s Mate, and Francis Drake, Trumpeter of

the Mary. And after the Muck, Java, or Devill, had ended the first part

of this bloody Tragedy, there was only left in the ship, the Cooke, 3

Boyes, and one John Taylor, that was almost dead with a shott he

foolishly made. So that 7 men were unfortunately lost (as you have

heard) and the Gunner escaped very narrowly through God’s merciful

prevention, from the like of these related disasters and suddaine

mischiefs, Good Lord deliver us.’

The engraving,

like all those belonging to this period, is very rough; but it was

evidently prepared specially for the occasion, and some care appears to

have been taken to represent the ‘Java’ as he is described. It is a

genuine attempt to illustrate the story, and on that account is more

interesting than some of the woodcuts in the early newspapers.

The

Earl of Strafford, who was executed on Tower Hill, May 12, 1641, forms

the subject of more than one illustrated tract of this period. In 1642

was published a curious pamphlet, consisting of an engraved title and

eight pages of illustrations, representing the principal events of

1641-2. There are sixteen illustrations, exclusive of the title, two on

each page. They are all etched on copper, and are done with some freedom

and artistic ability. I shall have occasion to refer to this pamphlet

hereafter; but at present I have copied the engraving entitled, ‘The

Earle of Strafford for treasonable practises beheaded on the

Tower-hill.’

|

| EXECUTION OF STRAFFORD, 1641 |

In

this example of illustrated news the artist has faithfully represented

the locality in his background, but there the truth of his pencil stops.

Strafford himself, although his head is not yet severed from his body,

lies at full length on the scaffold, and instead of the usual block used

for decapitations the victim’s head rests on an ordinary plank or thick

piece of wood. There is no one standing on the scaffold but the

executioner, whereas history asserts that the Earl was attended in his

last moments by his brother, Sir George Wentworth, the Earl of

Cleveland, and Archbishop Usher. These omissions, if they were noticed

at all, were no doubt looked upon as trivial faults in the infancy of

illustrated journalism, and before a truth-loving public had learnt to

be satisfied with nothing less than ‘sketches done on the spot.’ What

appears to be a more correct view of the execution was, however,

published at the time. In the British Museum are two etchings by Hollar

(single sheets, 1641), representing the trial and execution of the Earl

of Strafford. They both look as if they had been done from sketches on

the spot, that of the execution giving a correct view of the Tower and

the surrounding buildings, but they are too crowded to admit of

reproduction on a reduced scale.

The taste of the time

tolerated the publication of satires and petty lampoons even upon dead

men. Soon after Strafford’s death a tract was published entitled ‘A

Description of the Passage of Thomas, late Earle of Strafford, over the

River of Styx, with the Conference betwixt him, Charon, and William Noy.’ There is a dialogue between Strafford and Charon, of which the following is a specimen:—

‘Charon.—In

the name of Rhodomont what ayles me? I have tugged and tugged above

these two hours, yet can hardly steere one foot forward; either my dried

nerves deceive my arme, or my vexed Barke carries an unwonted burden.

From whence comest thou, Passenger?

‘Strafford.—From England.

‘Charon.—From

England! Ha! I was counsailed to prepare myselfe, and trim up my boat. I

should have work enough they sayd ere be long from England, but trust

me thy burden alone outweighs many transported armies, were all the

expected numbers of thy weight poor Charon well might sweat.

|

| STRAFFORD CROSSING THE STYX, 1641 |

‘Strafford.—I bear them all in one.

‘Charon.—How?

Bear them all in one, and thou shalt pay for them all in one, by the

just soul of Rhodomont; this was a fine plot indeed, sure this was some

notable fellow being alive, that hath a trick to cosen the devil being

dead. What is thy name?

‘(Strafford sighs.)

‘Charon.—Sigh

not so deep. Take some of this Lethæan water into thine hand, and soope

it up; it will make thee forget thy sorrows.

‘Strafford.—My name is Wentworth, Strafford’s late Earle.

‘Charon.—Wentworth!

O ho! Thou art hee who hath been so long expected by William Noy. He

hath been any time these two months on the other side of the banke,

expecting thy coming daily.’

Strafford gives Charon but

one halfpenny for his fare, whereat the ferryman grumbles. Then ensues a

conversation between Strafford and William Noy, part of which is in

blank verse. The tract is illustrated with a woodcut, representing

Strafford in the ferryman’s boat with William Noy waiting his arrival on

the opposite bank.

|

| A BURLESQUE PLAY ABOUT ARCHBISHOP LAUD. ACT I. 1641 |

No

man of his time appears to have excited the hostile notice of the press

more than Archbishop Laud. The Archbishops of Canterbury had long been

considered censors of the press by right of their dignity and office;

and Laud exercised this power with unusual tyranny. The ferocious

cruelty with which he carried out his prosecutions in the Star Chamber

and Court of High Commission made his name odious, and his apparent

preference for ceremonial religion contributed to render him still more

unpopular. Men were put in the pillory, had their ears cut off, their

noses slit, and were branded on the cheeks with S. S. (Sower of

Sedition), and S. L. (Schismatical Libeller). They were heavily fined,

were whipped through the streets, were thrown into prison; and all for

printing and publishing opinions and sentiments unpleasing to Archbishop

Laud, under whose rule this despotic cruelty became so prevalent that

it was a common thing for men to speak of So-and-so as having been

‘Star-Chambered.’ No wonder, when the tide turned, that the long-pent-up

indignation found a vent through the printing-press. Amongst the

numerous tracts that were published after the suppression of the Star

Chamber were many which held up Laud to public execration. He was

reviled for his ambition, reproached for his cruelty, and caricatured

for his Romish sympathies. During the four years between his fall and

his execution, portraits of him and other illustrations relating to his

career may be found in many pamphlets. I propose to introduce the reader

to some of these, as examples of the kind of feeling that was excited

by a man whose character and actions must have contributed not a little

to bring about a convulsion which shook both the Church and the throne

to their foundations. It must have been with a peculiar satisfaction

that Prynne, one of the chief sufferers under Laud’s rule, found himself

armed with the authority of the House of Commons to despoil his old

enemy. Probably a similar feeling caused many others to chuckle and rub

their hands when they read, ‘A New Play called Canterburie’s Change of Diet, printed in 1641.’

This is a small tract illustrated with woodcuts, and is written in the

form of a play. The persons represented are the Archbishop of

Canterbury, a doctor of physic, a lawyer, a divine, a Jesuit, a

carpenter and his wife. The doctor of physic is intended for either Dr.

Alexander Leighton, or Dr. John Bastwick, both of whom had their ears

cut off; the lawyer is Prynne; and the divine is meant for the Rev.

Henry Burton, a London clergyman, who also suffered under Laud’s

administration. In the first act enter the Archbishop, the doctor, the

lawyer, and the divine. Being seated, a variety of dishes are brought to

the table, but Laud expresses himself dissatisfied with the fare placed

before him and demands a more racy diet. He then calls in certain

bishops, who enter armed with muskets, bandoleers, and swords. He cuts

off the ears of the doctor, the lawyer, and the divine, and tells them

he makes them an example that others may be more careful to please his

palate. On the previous page is a copy of the cut which illustrates the

first act.

|

| A BURLESQUE PLAY ABOUT ARCHBISHOP LAUD. ACT II |

|

| A BURLESQUE PLAY ABOUT ARCHBISHOP LAUD. ACT III. |

In

the second act the Archbishop of Canterbury enters a carpenter’s yard

by the waterside, and seeing a grindstone he is about to sharpen his

knife upon it, when he is interrupted by the carpenter who refuses to

let him sharpen his knife upon his grindstone, lest he should treat him

(the carpenter) as he had treated the others. The carpenter then holds

the Archbishop’s nose to the grindstone, and orders his apprentice to

turn with a will. The bishop cries out, ‘Hold! hold! such turning will

soon deform my face. O, I bleed, I bleed, and am extremely sore.’ The

carpenter, however, rejoins, ‘But who regarded “hold” before? Remember

the cruelty you have used to others, whose bloud crieth out for

vengeance. Were not their ears to them as pretious as your nostrils can

be to you? If such dishes must be your fare, let me be your Cooke, I’ll

invent you rare sippets.’ Then enters a Jesuit Confessor who washes the

bishop’s wounded face and binds it up with a cloth. There is also an

illustration to this act which is here copied.

|

| ASSAULT ON LAMBETH PALACE, 1642 |

In

the third act the Archbishop and the Jesuit are represented in a great

Cage (the Tower) while the carpenter and his wife, conversing together,

agree that the two caged birds will sing very well together. The woodcut

to this act represents a fool laughing at the prisoners.

There

is a fourth act in which the King and his Jester hold a conversation

about the Bishop and the confessor in the cage. There is no printer’s or

publisher’s name to this play, only the date, 1641.

The

pamphlet previously referred to as containing a picture of Strafford’s

execution, has also an engraving showing how the tide of public feeling

had set against Archbishop Laud. The powerful Churchman had been

impeached for high treason; he was deprived of all the profits of his

high office and was imprisoned in the Tower. All his goods in Lambeth

Palace, including his books, were seized, and even his Diary and private

papers were taken from him by Prynne, who acted under a warrant from

the House of Commons. The engraving under notice is entitled ‘The rising

of Prentices and Sea-men on Southwark side to assault the Archbishops

of Canterburys House at Lambeth.’

In a tract entitled ‘A Prophecie of the Life, Reigne, and Death of William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury,’

there is a caricature of Laud seated on a throne or chair of state. A

pair of horns grow out of his forehead, and in front the devil offers

him a Cardinal’s Hat. This business of the Cardinal’s Hat is alluded to

by Laud himself, who says, ‘At Greenwich there came one to me seriously,

and that avowed ability to perform it, and offered me to be a Cardinal.

I went presently to the king, and acquainted him both with the thing

and the person.’ This offer was afterwards renewed: ‘But,’ says he, ‘my

answer again was, that something dwelt within me which would not suffer

that till Rome were other than it is.’ It would thus appear that the

Archbishop did not give a very decided refusal at first or the offer

would not have been repeated; and that circumstance, if it were known at

the time, must have strengthened the opinion that he was favourably

inclined towards the Church of Rome. At all events, the offer must have

been made public, as this caricature shows.

Though Laud

behaved with dignity and courage when he came to bid farewell to the

world, if we are to believe the publications of the time, he was not

above petitioning for mercy, while any hope of life remained. In 1643 a

pamphlet was published with the following title, ‘The Copy of the

Petition presented to the Honourable Houses of Parliament by the Lord

Archbishop of Canterbury, wherein the said Archbishop desires that he

may not be transported beyond the Seas into New England with Master

Peters in regard to his extraordinary age and weaknesse.’ The

petition is dated ‘From the Tower of London this 6th of May 1643,’ and

in it the petitioner sets forth that out of a ‘fervent zeal to

Christianity’ he endeavoured to reconcile the principles of the

Protestant and Roman Catholic religions, hoping that if he could effect

this he might more easily draw the Queen into an adherence to the

Protestant faith. He deplores that his endeavours were not successful,

and he begs the honourable Parliament to pardon his errors, and to

‘looke upon him in mercy, and not permit or suffer your Petitioner to be

transported, to endure the hazard of the Seas, and the long

tediousnesse of Voyage into those trans-marine parts, and cold

Countries, which would soon bring your Petitioners life to a period; but

rather that your Petitioner may abide in his native country, untill

your Petitioner shall pay the debt which is due from him to Nature, and

so your Petitioner doth submit himselfe to your Honourable and grave

Wisdoms for your Petitioners request and desire therein. And your

Petitioner shall humbly pray &c.’

|

| CARICATURE OF THE DEVIL OFFERING LAUD A CARDINAL’S HAT, 1644 |

If

Archbishop Laud was really the author of this petition he appears to

have expected that his long imprisonment would end in banishment rather

than death. He was beheaded on Tower Hill, January 10, 1645. There is a

woodcut portrait of the Archbishop printed on the title-page of the

petition.

|

| ARCHBISHOP LAUD |

[from Allan: reading through the rest of this book, I’m seeing that the author is far more interested in reprinting odd and interesting woodcuts from these ancient publications, along with long extracts from the texts, and the actual HISTORY of the publications and art is getting very little coverage. I thought there was much more meat about publications and techniques than I’m now seeing. Therefore I’ve decided to cut the book off here, as it is not what I really wanted to showcase here. If you’d like to read more of this interesting book, you’ll find it available from archive.org.]